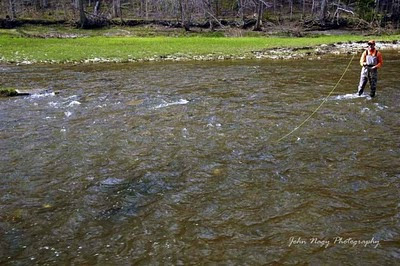

New entries to the sport of fly fishing are routinely bombarded with the importance of fly casting (distance, line speed, etc.) to catch fish with not much emphasis on wading strategies

v

In Great Lakes steelhead fishing, wading strategies are often more important versus fly casting to consistently catch steelhead on the tributaries

A good strategy for the steelheader (before just "jumping" into the river) is to plan his or her wading path and final positioning before making a fly cast to a specific “target zone”. A target zone (TZ) will contain a current break in the stream flow which steelhead use for resting during their upstream migration in the fall and also as a holding area prior to spawning in late winter, early spring.

v

A well thought out wading plan can result in a more effective initial fly cast (s) to the target zone and also allow for better line control and mending. This will ultimately result in a more effective dead-drift or swing presentation to the steelhead and a higher probability of an initial hook-up.

v

My mantra as a steelhead guide on the Lake Erie tributaries over the years has always been to “get them on the first, second or third drift”. Remember that the more bad drifts over a steelhead you make (dragging on the bottom and drifting over their heads for dead-drift presentations or swinging your fly too fast or slow on the swing) the more you turn a steelhead “off” to striking your fly.

v

High-Stick Nymphing

v

In “high-stick” nymphing, whether bottom-bouncing or using a floating indicator, wading and positioning is everything in order to achieve flawless drag-free drifts on or near the stream bottom (where steelhead can be found the majority of the time). Fly casting at distance is detrimental to dead-drift presentations because a large amount of fly line can get into the water interfering with a drag-free drift.

v

Better to wade as close as possible to the TZ and use a “short-line” approach to minimize fly line interference. This will result in much better line mending and line control over the dead-drift. Many Great Lakes tributaries are rather shallow making this close-in wading very feasible. Also post run-off stain (which gives steelhead a sense of security in shallow water) allows for wading in close proximity to steelhead lies as well.

v

Before you begin wading, locate potential steelhead resting and holding areas by “reading” the water and observing any surface texture changes which would indicate current breaks below. Polarized sunglasses come in handy for cutting the glare on the water and picking-up even the subtlest surface texture variations.

v

These TZ areas (which I also call “sweet spots”) are very specific and localized, are slightly slower than the surrounding current flow and have the right depth/clarity to give steelhead a sense of security. They can be found at current breaks created by shale ledges and man-made structures, in streambed depressions, pool tail-outs, slower areas in runs and eddies, behind rocks/boulders in pocket water areas and along downed timber.

v

After wading into position, stand directly in front of the TZ, but not too close that it inhibits fly line/leader control. Cast a relatively short line (30 feet or less) upstream, following up with a mend(s) and a high-stick rod position, which helps minimize fly line contact with the water. Repeat drift several times and then take a few steps downstream and start over. (See John Nagy’s Steelhead Guide Book for a more detailed explanation of high-stick nymphing and other steelhead presentations).

v

Swinging

v

Swinging presentations require a completely different wading strategy versus a dead-drift presentation. Swinging also allows the steelheader to see the river in a larger view, both downstream and bank-to-bank, as he fishes. It is quite a different experience versus the more localized and focused dead-drift method.

v

Again, read the water first to locate likely steelhead lies. Ideal steelhead resting and holding areas for swinging (versus dead-drifting) are much larger and are conducive for being covered with a swinging presentation. They include current breaks at the head of pools, along parallel “seams” that run through pools/runs and also in pool tail-outs. Positioning yourself by wading above the TZ (easily done on many Great Lakes tributaries which are rather shallow) will allow you to effectively swing your fly “down-and-across” to steelhead.

v

Begin the swing by casting your fly line at a 45 degree angle downstream to the left or right of the TZ. For a single-handed cast (with a sinking leader or sink tip line) using a single or double-haul, followed by shooting the line, makes this easy.

v

To methodically cover a pool or run after the initial swing is made with the fly, lengthen subsequent casts in increments of a foot or so until you have satisfactorily covered the TZ. Next, take a few steps downstream and begin the entire sequence again.

v

Most steelhead take the fly at the end of the swing (more likely chasing the fly across the current and hitting it from the rear as it stops) so it is important to anticipate the strike at that point.

v

The strength of the current and depth of the river (as well as how strong of a wader you are) will determine how precisely you can position yourself above the TZ and also work your way downstream. Wading to a position slightly to the right or left (and above) is ok, as long as you can get the proper angle on your cast to the target area and swing through the target area.

v

The temptation by most steelheaders swinging flies (especially double-handed casters) is to immediately wade into the head of pools and runs, throw a long line downstream and begin the swing presentation at TZ’s at distance. The problem is you will miss great opportunities to catch steelhead "close-in" with this strategy (duh, your standing on top the steelhead!) Also, swing presentations done at long distances can make precise downstream line mending and control difficult, which can prevent you from getting proper fly speed and fly depth on the swing.

v

Be patient and work close areas first (you will need to position yourself far back enough to do this close-in swing properly). Steelhead will hold amazingly close, especially early in the morning, on overcast days and in heavily stained water.

v

Switch Rods

v

“Switch” type fly rods can make swinging flies for the Great Lakes steelheader an easy proposition. Close-in and medium range distances can easily be done using these rods single-handed. When distance is needed (when wading in higher run-off flows and wading/swinging your way down into deeper pools and runs) as well as when back casts are not practical due to obstructions, reaching down to the lower handle for a “double-hand assist” allows for double-handed over head casts and spey style casts.

These fly rods are also ideal for high-stick nymphing due to their long lengths, with some manufacturers offering more moderate actions that are ideal to protect lighter tippets when nymphing.

v

Safe Wading on the Tributaries

v

Here are a few safe wading practices to remember when wading on the tributaries:

v

-Always use a wading belt with chest waders. If you take a dunking the wading belt will prevent the waders from filling with water and keep you afloat till you can climb out downstream.

v

-Polarized sunglasses are essential for seeing rocks, ledges, holes, etc. while wading. If the tributary flow is stained and visibility is poor, slowly shuffling your feet and “feeling” the bottom as you go will prevent missteps and tripping.

v

-Before wading a tributary in higher flows, learn the streambed “topography” for that tributary when the water is low and clear. This will not only help you safely wade the tributary (you’ll know where all the shallow crossings are) but will also show ideal steelhead holding areas such as ledge drop-offs, streambed depressions and shale cuts.

v

-In higher tributary flows, cross the river slightly upstream, at an angle and leaning into the current (don’t let the current hit you directly from behind the knees).

v

-You can get into a heap of trouble very quickly wading a tributary downstream in higher flows (especially when the river drops off quickly as you go downstream).

v

-Be aware of steep/loose gravel bars that can break apart when wading and slide you into deeper water.

v

-Monitor water levels (and weather reports) closely before crossing a tributary. Run-off from rainfall and snow-melt (and unexpected dam releases) can quickly raise tributary water levels and trap you on the wrong side of the river.

v

-Studded boots and/or wading staffs are musts for the tributaries (particularly the larger ones) during high/stained run-off. For added safety, wearing an inflatable PFD can provide instant floatation with the pull of a lanyard. Stearns makes an inflatable fishing vest/chest pack ideal for the steelheader. The new William Joseph WST Waders (wader safety technology) have an integrated inflatable bladder which allows you either manual or emergency CO2 inflation.

v

-The new rubber-bottomed wading boots like the light-weight Simms Rivershed boot (including Simms Hardbite Studs and Star Cleats) are ideal for winter steelheading. They will not accumulate snow and ice on the bottom when hiking snow covered tributary banks (which felt-bottomed boots are notorious for).

More detailed information on wading strategies for steelhead can be found in John Nagy's book "Steelhead Guide, Fly Fishing Techniques and Strategies for Lake Erie Steelhead".